Ice-told stories through layers of dust by Penelope Cain / A politics of the living by Ena Grozdanić

Penelope Cain

Penelope Cain's practice centres around land and water storytellings from the Anthropocene and Post-Carbon. These occupied, colonised, extracted and transformed lands, and the other-than-human future-fables and mythologies, as they emerge in this end-Anthropocene.

With a biological science background Penelope Cain's art practice is located between scientific knowledge and unearthing connective untold narratives in the world. She works across media and knowledge streams, with scientists, datasets, people, residues and land to map molecular-level connections between places, over oceans and across time. Forming present and near-future storytelling centring around pollutants, residues and extractions.

She was awarded the Fauvette Loureiro Travelling Scholarship, SCA University of Sydney, 2018, Glenfiddich Contemporary Art Residency 2019. Most recently she exhibited in Re/Wild, Maxxi Rome (2022) and in the SACO Biennale, Chile (2023). Raised in Adelaide, Penelope Cain lives and works between Sydney and the Netherlands.

Sift.

Let’s start with the lead-soaked dust. Harsh sharp gritty dust, which burns the throat and stings the flesh. To tell the story of the dust means starting 1,685 million years ago, in the Earth’s era of peak volcanic activity, when boiling seawater mixed with the cooler water above. It means considering the mineral-rich sediment, the next 500 million years of erosion, the Earth’s exposure to groundwater and air. This is how you get to the giant ore body—bursting with silver, lead and zinc—sitting one and a half kilometres below Broken Hill, on Wilyakali Country. When the first silver mine opened in 1885, settlers cut into the soil, sunk shafts, blasted rock and registered Broken Hill Proprietary Co. They hauled off trees, constructed fences, and built new mountains out of debris and gravel. Lead seeped out, chemicals poisoned the water supply, and the dust arrived. And dust, as we know, finds its way into windowsills, pavers, roads, airways and lungs. Dust and a strong breeze can drain a bright blue sky.

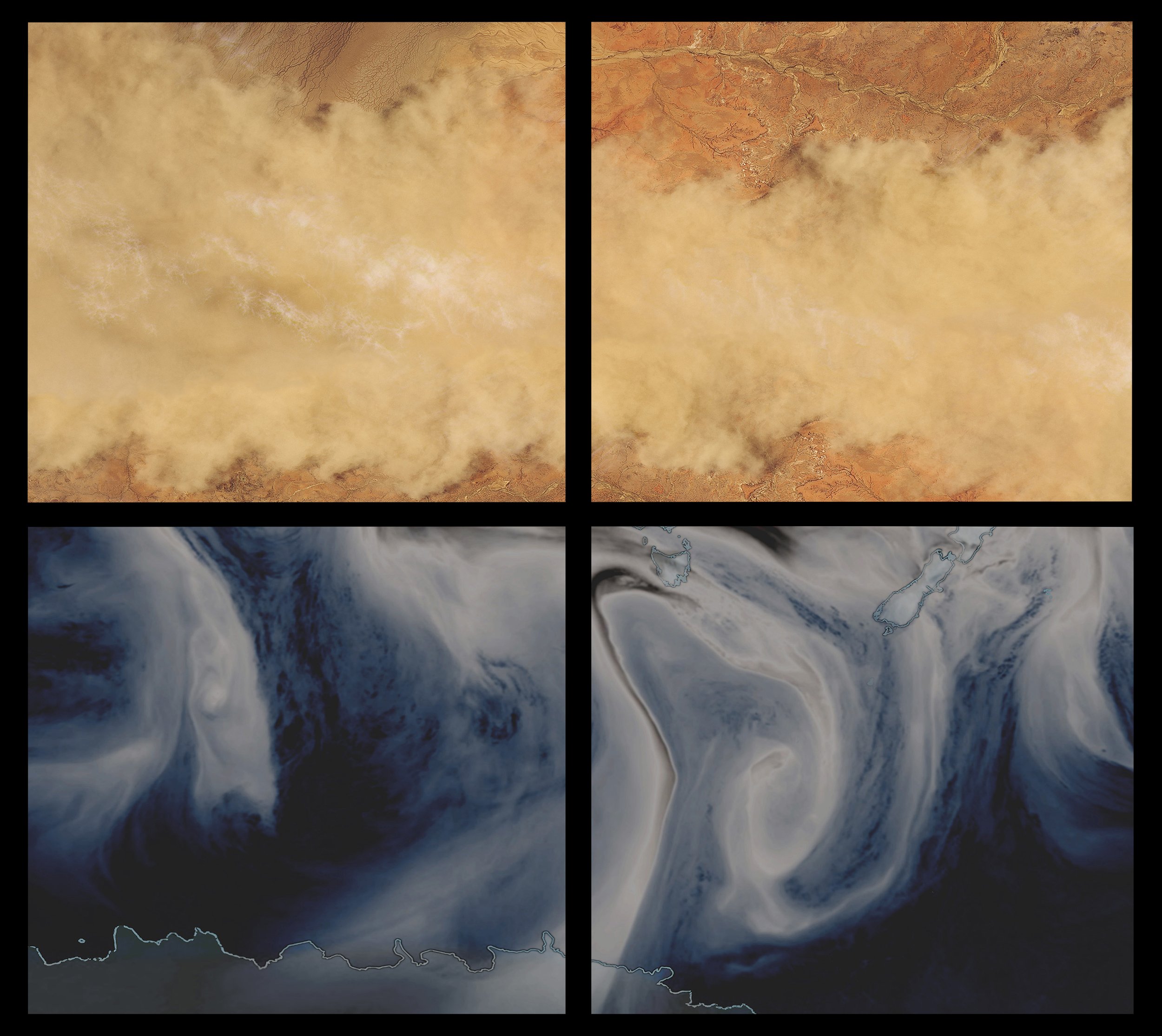

So, in 1889, when the wind picks up, the dust thinks, It’s time to see the world! And the toxic lead, the dust’s co-conspirator and travel companion, agrees and says, We’re wasted here! They gather themselves up on the surface of the Earth and begin their ascent into a whole new manner of being. Now they’re experiencing the wild ride of atmospheric aerosol circulation: they’ve found the whip of the current, the convoluted shuffle between high and low air pressure systems, the unexpected thrill of the jet stream. They’re moving southward at a clip, rushing towards the pole, hovering over the ocean, befriending vapour, fog and cloud.

The dust spies its destination. An atmospheric river drops, dumps, ejects it onto a white expanse. Twenty-two years before the race to discover the South Pole— Amundson with dogs, Scott with Siberian ponies—the ‘untouched’ continent is unceremoniously contaminated by the grey poisonous refuse of extractive economics. (We know this because lead, originating from Broken Hill, is visible in sixteen Antarctic ice-core record samples.)

Dust, as Andrea Barrett writes, “gathers and makes visible what is otherwise unseen”. What is the dust making visible here? That ice is also a memory-maker, a ledger of human extraction, a steadfast meteorologist. That the boundaries between air, water, earth, land, fence, border, inside and outside, are imaginary at best. The dust is saying to us, even as the ice melts: Wherever you may wish to go, know that I’ve already arrived.

Naomi Riddle

Naomi Riddle is a writer living on Gadigal Land and the founding editor of Running Dog.

Penelope Cain, Ice-told stories of lead and rope. Amundsen source material courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Penelope Cain, Ice-told stories of rivers and wind.

Penelope Cain, Ice-told stories of canyons and rock.

Ena Grozdanić

Ena Grozdanić (she/her) is a writer and emerging artist living on unceded Kaurna land. She is Editor at Runway Journal, and is a former Co-director of FELTspace. She was also an original member of independent artist-run publication KRASS Journal. Her practice spans text, video, sound, collage, and installation. Ena has had bylines in national and international publications. She has exhibited at Watch This Space (Mparntwe/Alice Springs), Pari (Dharug Land/Sydney), Cool Change Contemporary (Boorloo/Perth), Performance Space’s Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art 2022 (Gadigal Land/Sydney), and FELTspace (Tarntanya/Adelaide), amongst others. Her sound work ‘Timesick’ was recently part of Radio Elsewheres at the KRAK Centre for Contemporary Culture (Bosnia and Herzegovina), and she has participated in residencies at Testing Grounds (Naarm/Melbourne), Can Serrat (Spain) and elsewhere. She will be screening work in the Seventh Cinema program (Naarm/Melbourne), and has an upcoming solo exhibition at TCB (Naarm/Melbourne). Ena is currently fascinated by the ethics of remembrance, particularly in relation to lost worlds, interrupted histories, and disappearing landscapes. She has ongoing research projects that ask critical questions about language, place, and land-as-commodity.

In Samuel Beckett’s final play, Happy Days, a woman (Winnie) is trapped in waist-deep sand—her husband (Willie) is close behind. On stage is a large black bag and nothing else. Over the course of the play, the sand continues to rise, with all that implies. She entertains herself, or us, by going through the contents of the bag, which become a kind of memory aid.

Frequently, she uses the term “Old Style”. Beckett, for whom Happy Days was indeed an attempt at optimism, uses the term to allude to the way that the war, some 15 years prior, had cleaved a temporal boundary between now and then. What can those stuck enduring its aftermath cling to but their humour? Winnie’s tone is tragic, which is distinct from defeated (though this is often misunderstood). I’m reminded of James Baldwin here: “White Americans seem to feel that happy songs are happy and sad songs are sad, and that, God help us, is exactly the way most white Americans sing them— sounding, in both cases, so helplessly, defenselessly fatuous.”

The music box plays the waltz duet from Franz Lehár’s 1905 operetta, The Merry Widow, while the parasol sets on fire, and Winnie goes on talking. “That is what I find so wonderful. The way man adapts himself. To changing conditions.”

She has more courage than Willie; she is the hero of the play.

I’m thinking of Happy Days as the specter of world war becomes impossible to ignore. As the routines of our daily lives seem ever more absurd, given the context we find ourselves in, and as the sand proverbially mounts all around us. I’m writing from the New York Public Library, and beside me is the March issue of Harpers Magazine; I’ve opened the page to their Index Column, which lists statistics across a multitude of subjects, evidently intending to suggest a whole picture of the ‘moment.’ The first two claims: 76% of professors at U.S. universities report feeling the need to self-censor when talking about the war in Gaza; 96% of graduate students claim the same. But refusal defies such easy legibility or codification. In a few hours, I’ll attend a vigil for the soldier who self-immolated while repeating “Free Palestine.”

The collages exhibited by Ena Grozdanić invoke both war and rebellion. Objects scanned and digitally manipulated are removed from their context to reference disparate historical events. The text “death to fascism freedom to the people” was the slogan of the Yugoslavian Partizan revolution — fragments from the counter-revolution are evident elsewhere (flowers for the dead; an empty field; an old clock). This speculative engagement with history holds something like a liberatory suggestion: if the past is contestable, the future might be as well.

Elsewhere in this exhibition, Ena references more directly. One work begins with the repetition of the moments before the US drone strike that murdered Mamana Bibi in Pakistan. Repetition can be a kind of insistence — it can be a way to memorialize, eulogize, and raise specters. These works, taken together, seem to emphasize a different relationship between history and memory — one in which the past is unfinished or unresolved. In so doing, they allow us to ask pertinent questions about what gets lost, forgotten, discarded, and then, too, what gets archived as history. What emerges is indeed a politics of the living.

Sanja Grozdanić

Sanja Grozdanić is a writer based between Berlin and New York City.

Ena Grozdanic, 2024, A Politics of the Living (indicative), scanned objects, digital collage

Ena Grozdanic, 2024, A Politics of the Living (indicative), scanned objects, digital collage

Ena Grozdanic, 2024, A Politics of the Living (indicative), scanned objects, digital collage

Ena Grozdanic, 2024, A Politics of the Living (indicative), scanned objects, digital collage