Resourceful Women & Desperate Stratagems by Christina Peek / Somewhere, something by Kate Kurucz

Christina Peek

Christina Peek is an emerging visual artist living and working on Kuarna land, South Australia. She graduated from the Adelaide Central School of Art in 2016 with Honours. Peeks practice explores the juxtaposition between romantic narratives and lived experience. In 2016 she had her first solo show at FELTspace and was the recipient of the FELTspace Philanthropic Fund. In 2018 she created a new body of work in collaboration with Adelaide artist Edwina Cooper for Floating Goose Gallery and exhibited at From Adelaide With Love at Sawtooth Artist Run Initiative in Launceston.

The fairy tales we’re most familiar with are grandiose and fantastic, centred on princes or princesses, castles or dragons, mythical creatures and true love and just endings. Most are candy sweet in a way that leads us to gorge ourselves on them as children, and insubstantial enough that they rarely sustain us when we reach adulthood. All survive in part because of the lesson they impart in the service of social order, sitting in a pantheon alongside folklore, parables and other cautionary tales. While perhaps modern fairy tales focus on happy endings, the fables that Peek has chosen as starting points are tainted with tragedy, teaching us that the road to a happy ending is often paved with hardships and heartbreaks, and that every misdeed, no matter how trivial, has its consequence. We learn that just as fate favours the prepared, love or magic seldom comes to those who wait. They’re stories and calls to action, leading us to actively manifest our desires, to know that agency and tenacity are rewarded more often than patience and modesty.

The fairy tale has been an agent and driver of change since its genesis in oral traditions. The ability to be adapted is what makes these stories a perfect tool for change, as just as each storyteller introduces shifts in tonality and meaning which accumulate over time, our ability and willingness to shape these stories around ourselves invariably leads them to reshape our experience and understanding of the world in kind. In that sense, these works are another iteration of this process of retelling in which understandings of love and magic are reconfigured for both storyteller and subject, revealing and generous in equal measure.

Here, Peek translates familiar concepts of love, magic and labour from the unfamiliar tongue of strange, bygone fables into a language of her own making. They are sensuous and unexpected, asking us to shift our relationship with these things from one of wishing or hoping to one of grasping. Love becomes something we must discover again, realising that love is not just in the rose that blooms, but in the soil that nourished it, the clearing of weeds, the buried leaching in the ground to foster such fertility. Fairy tale love is transformational, and here transformation has its own kind of violence, a violence enacted upon love when the story strips it of all finery and civility to reveal the primal and then enacted upon us when this revelation reveals us in kind. For just as love is at the heart of these things, so too is it in ours.

To be transformed by these stories is to relearn love and magic; to realise that real magic is the kind that lives in creation, in the way a woman’s hands take flour and make bread, in the way her body takes a man’s essence and crafts him a son. It’s intertwined with the feminine, with natural cycles and domesticity, with labour that uses whatever is at hand, recreating the world in ways that are well within our reach. These realisations, of the connection between creation, labour and magic, can be both liberating and terrifying; we learn that we could shape the world with the most modest of materials and that others could do the same. We covet and fear it in equal measures.

These stories teach us that both magic and love, are ambivalent, good and bad, solicitous or overwhelming depending on circumstance or standing. At times magic is more in the answer than the invitation, a thing catalysed by the action of our desires but that lives in the reaction. This kind of magic starts with a young woman’s frustrated wish for a lover, the desperate plea that the bodies we craft be blessed with soul, but it lives in the devils that answer wishes and the words that undo them, in the benevolence and indifference of Gods. Sometimes magic is in neither invitation nor answer but is instead a forceful change. It lives in the crafted phallus that beguiles a young paramour or the lover crafted from blubber and revitalised through sex, over and over with no respect to death or endings. The magic that grants effigies a soul is the same kind that leaves these effigies to melt in the high sun, just as the devotion that wears iron boots to nothing is the same devotion whether the wearer be lover or devil.

It’s magic that makes the masterpiece and the failure, obsession and ambivalence, every work that we see and every work that we don’t. We learn that love is the impetus for creation and for magic, for these works that Peek has made with her hands and drawn with her mind, in the tears that paid the price for their soul, in the satisfying completion of this great labour. Love, we learn, and magic and devotion, are all within our reach if we try hard enough, down a path paved with labour that these works are more than willing to guide us down, a simple matter of the right method with the right amount of yearning. We arrive at these works with love in our hearts and leave with it in our hands, infected by the transformational magic that lives in these works that ensures we end markedly different than when we started.

Jess Taylor

Artist & arts writer

Christina Peek, East of the sun and west of the moon (detail), 2021, metal and ribbon, dimensions variable, photography Steph Fuller.

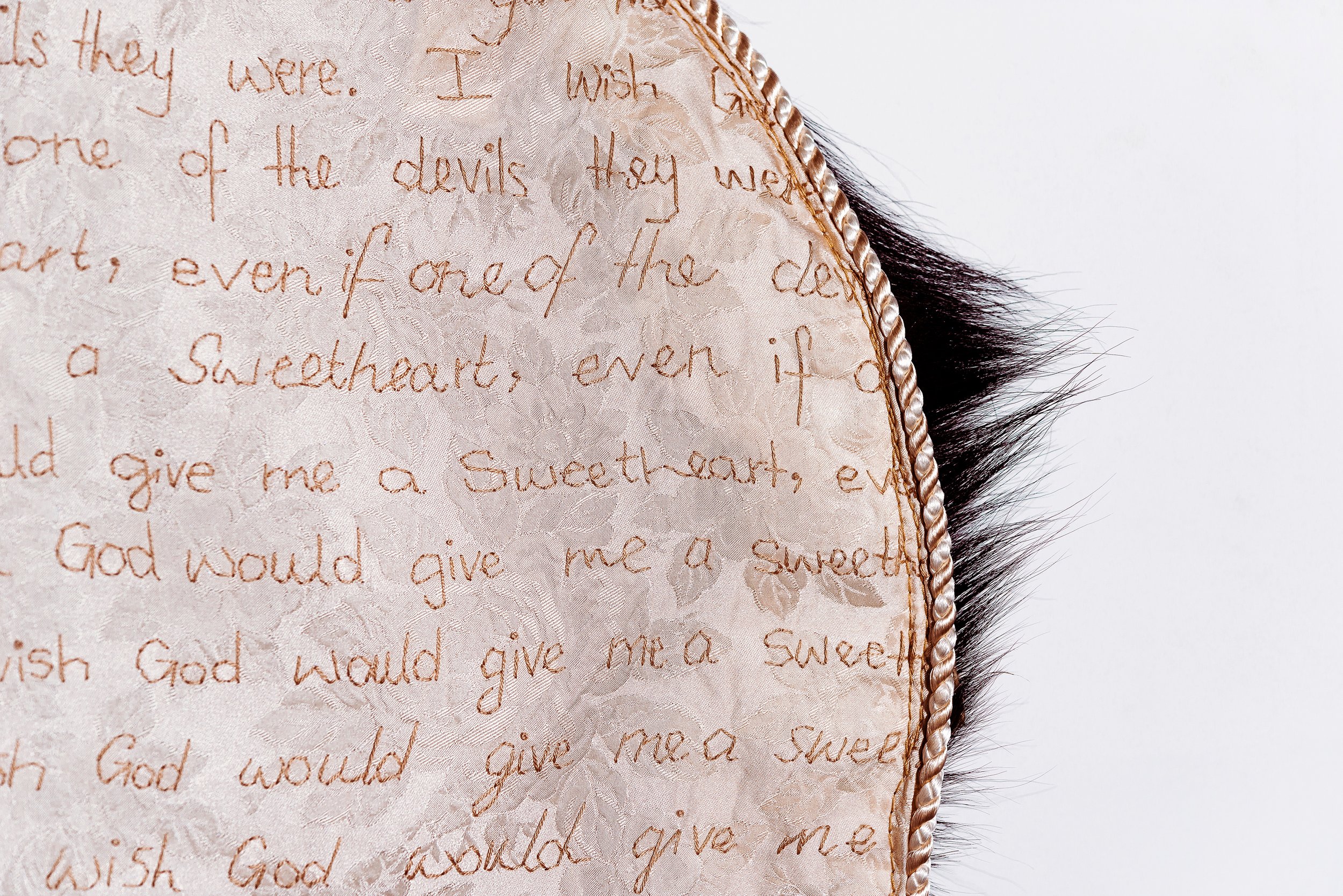

Christina Peek, …even if one of the devils they were (detail), 2021, goat skin, silk, cotton thread, cording, ribbon, 75 x 110cm, photography Steph Fuller.

“Did you ever look up at the night sky and feel certain that… not only was something up there but… it was looking down on you at the exact same moment just as curious about you as you are of it.” Agent Fox Mulder, The X-Files. [1]

Forty-four years ago, mankind sent a message out into space.

Etched in copper and plated in gold, the Golden Record was inscribed with a collection of sights and sounds of life on Earth. This phonographic record is a compendium of natural and manmade sounds – from volcano eruptions, through an advent of modern technologies, to compositions by Ludwig van Beethoven and Mozart. On its final spin, the record needle ripples across the shimmering surface to leave one final dedication: “To the makers of music—all worlds, all times.” [2]

Perhaps even louder than any earthly sounds though, is the gesture itself; the record thrums with the innate human desire to know and to be known. The Golden Record represents a modest but noble gift, like sharing a favourite song with a friend and expecting nothing in return.

It is one of the greatest of human compulsions to seek connection, to share the narrative of one’s life with others. This is a sentiment felt acutely by painter Kate Kurucz, whose artistic oeuvre is deeply rooted in the origins of human connection, of impulse and desire. As with the Golden Record, these works are a gift, proffered up by the artist without certain hope of return or reciprocation.

Resembling Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (c. 1508-1512), Kurucz paints two hands reaching longingly towards one another across a dark void interwoven with luminescent blue lines. These reference a Lissajous figure, a graphic representation created by a radio frequency machine. For Kurucz, this machine speaks of the optimism of retro futurism and is a suggestion that contact is simply just around the corner.

And indeed contact is closer than it seems in Always a bridesmaid. With a sardonic wit, Kurucz skews the narrative of an alien abduction by showing the UFO beaming up an unsuspecting bee and ignoring the reclining woman who looms in the foreground. Kurucz challenges our imagined self-importance, rupturing the narcissistic notion that we must be the sole object of extra-terrestrial desire. The truth, that we are but specks in a vast cosmic arena, is revealed in sublime scale.

In the recent Netflix Documentary John Was Trying to Contact Aliens, John Shepherd chronicles his 30 year quest to connect with extra-terrestrial life. Up until 1998, Shepherd literally beamed music millions of miles into space from the front garden of his grand-parents’ home.

“I was always seeking to explore, to look beyond what we have here. I pictured many alien worlds, imagining what it would be like to make contact. The moment of sharing extreme knowledge and thoughts and communication with another species… is just beyond anything most of us even imagine.” [3]

Growing up in rural Michigan during the 1960s, as a young gay man, John led an isolated life. Indeed, it is paradoxical to think that what John sought for so many years was connection and yet his search led him along a lonely life – until finding it with his partner, also named John.

As John Shepherd signs off in the 16 minute documentary, he talks about finally finding connection, albeit not a cosmic one: “I was one of the lucky ones. I feel I found it. Found it in John. So contact has been made”. It is this story of love and longing that manifests in Kurucz’s work Contact was made, depicting a lovers embrace silhouetted by a window from which a UFO hovers in the distance.

Just like the Golden Record, this work has been painted on the very stable and durable medium of copper. Its preservation ensured by the copper, the warm tones also provide a gentle and otherworldly glow as in the painting Curiosity. The juxtaposition of fine detail and loose slippery brushstrokes creates a dazzling effect that slips fluidly between realism and obscurity.

When working on linen, however, she claims control of the narrative. The atmospheric aesthetic in Always a bridesmaid is slower to unfold, and new tonal qualities are able to be discovered through distance and long looking. The fields of tone shift into focus to create a sense of depth and the vastness of the natural world beyond only heightens this.

In Somewhere, something Kurucz creates an illusory space that we as viewers are invited to leap into, untethered. For if there is one certainty, it is that human beings are ceaseless in their pursuit to find connection. While they may not be a glimmering Record hurled into the depths of space, Kurucz’s works give us a different form of communication, one that is rich with emotion. Perhaps one day into the not-so-distant future, we will look back on this exhibition and say: “contact was made”.

Contact was made by Gabi Lane

[1] Agent Fox Mulder in The X-Files, Season 3, Episode 12. 4 minutes: 31 seconds.

[2] Timothy Ferris, ‘How the Voyager Golden Record was Made’, The New Yorker, Aug 20. 2017.

[3] John Was Trying to Contact Aliens, 2020, Matthew Killip, 16 minutes, Netflix Original Documentary, US.

Kate Kurucz, For a good time call Gliese 445, 2021, Oil on copper, 45 x 45cm.

Kate Kurucz, Contact, 2021, Oil on copper, 70 x 45cm.